What is scenario planning?

Forecasting the future beyond the short term is inherently difficult. Even if we think we know how things work, we often lack sufficient information to make an accurate forecast. Countries, societies, economies etc are complex systems which can be inherently chaotic making it impossible to make accurate long term forecasts. A small change in the initial assumptions can lead to radically different predicted outcomes (see Systems thinking). One approach for dealing with this is to consider a range of possible futures or scenarios. While these may contain an element of forecasting, they are not intended to be predictions of the future. They serve two purposes. The first is to expose the range of uncertainty inherent in the forecasts that we can make. The second is to confront us with possible futures, that we have not considered, making us better prepared for the unexpected when it happens. Finally the process can widen our understanding of the world. In a business context scenario planning would normally sit alongside the strategic planning process as a way of test the resilience of a given strategy under different scenarios.

There are a variety of approaches possible but, as a starting point, a widely used framework was originally developed by Shell in the early 1970s and subsequently promoted by the now defunct consultancy Global Business Network. The approach was described in 'The Art of the Long View' by Peter Schwartz.

Drawing on this and my experience of scenario planning we might go through the following steps:

Step 1: Identify the focal issues or decisions

The importance of this stage is to keep the process focused. Without it there is a danger that the process will become sidetracked into considering issues that not relevent. This requires clarifing the goals to be achieved, the actions that can be taken and decisions made to achieve them. Clearly these will be very different for a global corporation, a small firm, a health care organisation, an individual etc. To summarise we need to identify:

- The goals that we are trying to achieve.

- The factors that we can control to achieve those goals – the levers.

- The factors which are beyond our control but which have a significant impact on achieving our goals – the external drivers.

For an organisation these goals may be quite clearly defined. For and individual, like me, they are more general and what can be done to enable my family and grandchildren to have a good life. I hope that viewers of this site will be able to use some of the things set out in it to address their own questions.

Step 2: Identify the external factors which could affect our decisions

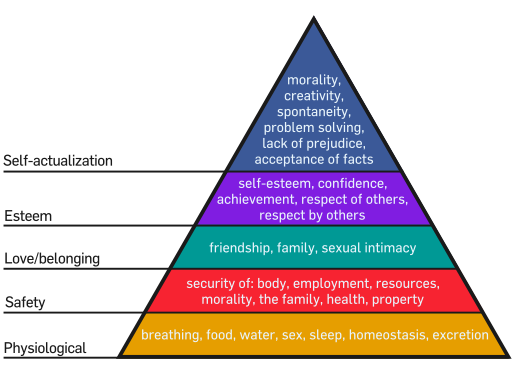

A company may be concerned about the market for the products, profits, tax etc. My more personal focus might focus on what is required for a good life. A possible starting poing for thinking about this is Maslow's hierarchy of needs:

What are the factors in our environment which could influence our ability to achieve these needs? E.g. availability of housing, jobs, education, healthcare, security from threats and crime, social opportunities etc.

Step 2: Analysis of the drivers of change

The second step is to identify and analyse the key change drivers which will have an impact on these external factors. A useful technique for ensuring that all aspects are covered is PEST(LE) analysis where drivers are grouped under the headings: Political, Economic, Social, Technical, (Legal, Environmental). A check can be made to ensure that all areas are adequately represented. In a corporate setting this might commonly be done as a group brainstorming event. E.g. people might write drivers on 'post-its' and stick them up on a board. Clustering can be carried out to link drivers that are very similar.

Impact/Uncertainty Analysis

Having identified drivers, it is important to identify which ones are likely to be the most significant for building our scenarios. The normal approach to this is impact/uncertainty analysis. Drivers are placed on a two dimensional grid identifying their likely level of impact on the issues we are addressing and also the level of uncertainty about how they will impact. What we are particularly interested in are those drivers which have high impact and high uncertainty since these are the ones which could produce very different future scenarios.

Timeline mapping

In addition to impact and uncertainty, it can also be useful to get views on how soon the different drivers or events might have an impact. A group of informed people might be asked to give their best estimates by placing each driver on a time line. This can be done either in a working group or using a technique such as Delphi.

Degree of control

Scenarios are about what we cannot control and strategies about what we can. At this point it is often useful to check that the drivers we have identified really are external in the sense that we cannot control them. Any that are fully under our control should be taken out and addressed in the strategy development process. Where we have limited or indirect control it may be useful at this stage to distinguish the elements within them that we can or cannot control.

Systems mapping

Drivers may not be independent of each other. A technique for teasing out how they might be interrelated is systems mapping where arrows are placed to show where one driver has a direct influence on another – these can be marked either positive or negative. For example the development of renewable energy systems or new technologies may solve climate change but will be limited by the availability of finance for investment, which in turn will depend on other social and political factors. Systems mapping can help to give a better idea of how things work when developing the scenarios and also underpin elements of systems modelling.

Step 3: Developing the scenarios

Scenario selection

The previous steps will have identified a whole range of drivers, their impact, uncertainty, when and how they might impact. The next step, which is the one which involves the greatest element of creativity, is using these drivers to generate a number of scenarios. It is important to remember at this point the scenarios are not forecasts, the aim is not to predict the future but to describe a number possible futures with the aim of challenging the assumptions in our strategies. Experienced scenario planners normally suggest avoiding the following types of scenario:

- The most likely scenario – the purpose of scenarios is to forearm us against the unexpected, a ‘most likely’ scenario will probably encourage us to ignore other possibilities as being less likely.

- Best, medium and worst scenarios – decision makers almost always prefer the best scenario and ignore the possibility that the worst scenario may be just as likely. It is much better to produce scenarios which have a mixture of good and bad elements.

- The official scenario – governments and senior management often have a set of assumptions which underpin their plans or policies. Unfortunately there may be a range of other equally likely scenarios which challenge these assumptions. To be effective in challenging strategies scenario planning needs to produce some plausible scenarios which differ from the official scenario. However, many scenario planners recommend describing the official scenario in order to get it out in the open before developing the alternatives.

The best scenario exercises produce several scenarios, all of which are significantly different from each other and all of which have elements that challenge our strategies. At the same time none of the scenarios should appear more attractive or more probable.

There are an infinite range of scenarios that can be developed from any set of drivers but it is normally recommended that the number of scenarios is limited to between three and five to make the process manageable. The usual technique for selecting which scenarios to build is to examine the drivers which were identified as having maximum impact and maximum uncertainty and try to develop a two or three dimensional matrix representing the most significant areas of uncertainty.

Scenario Creation

Having identified how the scenarios will be distinguished on the core dimensions, we might also wish to assign different values for other drivers to each of the scenarios. In this we might be guided by the systems mapping to see what values might belong together. The actual process of creating scenarios is a mixture of art and science. The group creating a scenario would be given a set of assumptions for values of the main drivers. From this they would start to construct a narrative describing a plausible world. In the process they are likely to develop the systems mapping that has already taken place to develop either descriptive or quantified models of how the world might work.

While it can be useful to have quantified assumptions to feed into our models, scenarios should also provide a detailed narrative description of the world and how it might work to help people imagine what it might be like to operate within it. This can be done through stories and the eventual aim of this website is do this.

Step 4: Testing strategies against scenarios

The final stage in the process is using the scenarios to test possible strategies. The aim is to produce a strategy which will achieve our goals even if a whole range of unexpected factors come into play. The best strategy, therefore, is the one which is able to achieve the goals under the widest range of scenarios. There might be a particularly good outcome in one scenario but we might prefer to go for a good enough outcome in all of them.

The testing process could involve quantitative modelling to test different assumptions on the values of key variables. Equally well it is likely to involve more descriptive analysis of the likely impact of each of the scenarios on the strategies.